I was driving home very late one night, north on the I-5, and moved over to the right lane where the ramp to the I-405 splits off with a sweeping curve that goes high in the air. Suddenly, there were no lane markers. I couldn’t see the edge of the road; there were no taillights in front of me; everything seemed to disappear. And, I was traveling about 70mph. It was PANIC! I stepped on the brakes, managing somehow to get off the unlit ramp, and back to lit roadway.

Why I put off cataract surgery

Why I put off cataract surgery

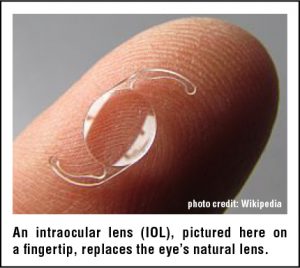

When driving at night, I had close calls before — being blinded by oncoming headlights or not being able to distinguish faded white lane markers. Although my ophthalmologist had been telling me for years that I needed to have cataract surgery, I kept putting it off. It was not from fear of the surgery, because cataract surgery is as common as the cold. But, my engineering brain needed to figure out the power of the lens implants (known as intraocular lens or IOL) that I would get. It would be a lifelong decision I didn’t take lightly.

I learned that with the typical cataract surgery, the power of the IOLs are chosen so that when combined with the lens power of your corneas, your vision is corrected to see sharply at far distances.

You should also note that the eye you’re born with has the power to adjust your vision by pulling on the natural lens with muscles that change its shape. The cataract stiffens the lens and makes that ability to adjust gradually disappear.

Monovision

“Monovision” means each eye is corrected to see sharply at different distances, rather than the same distance. Since the IOL has no ability to adjust, the IOL replacements for the natural lenses cannot enable someone to see clearly both close up and far away, as young people can do. So, a decision has to be made as to what distance each eye should be corrected to see. With monovision it is most common to have the IOLs selected so that one eye can see intermediate distances sharply and the other eye see far distances. For close-up viewing, eyeglasses would be required.

Since I spend ninety-five percent of my time at my desk, in my office or in my kitchen, I didn’t want to wear glasses for ninety-five percent of my waking time. I only want to wear glasses when driving, which is what I’ve done my whole adult life. So, with the enthusiastic cooperation of my ophthalmologist, Dr. Daniel Kline, of Irvine, he worked out two different resultant viewing distances for my two eyes, so I could see close-up with my left eye, and at intermediate distances with my right eye.

On December 19, 2018, a day I will never forget, I had surgery only on my right eye, the one with far worse vision. It would get an IOL with power to enable intermediate distance vision. Dr. Kline used laser equipment to perform the incision and to break up my cloudy, natural lens. I was amazed that immediately after the surgery I could see super-bright and colorful images I probably hadn’t seen in years. The degradation of my vision had been so gradual that I hadn’t noticed that what I thought was white had become yellow. Colors that were previously drab had become rich and vivid.

Amazing success!

Although my left eye was still highly myopic and clouded by the cataract, and my right eye was only corrected for intermediate distances (from 18” to about 39”), I put on a 30-year old pair of eyeglasses I found in my personal eyeglass museum, and they worked almost perfectly for driving. What I discovered during this experimentation phase is that when I closed my right eye while driving, everything was blurry through my left eye. And when I closed my left eye, everything was sharp and colorful through my right eye, although two-dimensional. When I then opened my left eye, the only thing that changed was that I could see three-dimensionally. Remarkably, my left eye did not add blurriness to my vision, only three-dimensionality. What I learned is that my brain automatically took what it needed from each eye to produce the best, most useful image, without my awareness!

So, with renewed confidence, three weeks later I had the cataract surgery on my left eye, this time so it could see close-up. And, as it turned out, I can now see sharply with my left eye from about 12” to about 18” and with my right eye from 17” to about 39.” With both eyes open (my typical viewing style) I can see very sharply from 12” to about 39”. Beyond that, to about 5 feet, things appear sharp enough for the items on my desk or my kitchen counter. I feel as if my pre-cataract vision has been fully restored!

As I go about my activities, I’m unaware of which eye is doing what. I did not have to get used to anything, or train myself to do eyeball or brain gymnastics. A few weeks after my second cataract surgery, I got a new pair of eyeglasses for driving.

However, I must report an anomaly that I experience in both eyes when driving at night. Oncoming headlights have bright halos. They’re not enough to blind me, but it is disturbing, although I had much worse halos with my cataracts. I’m working with my ophthalmologist as well as Alcon, the manufacturer of my IOLs, to see if we can figure out the cause. And if not, my vision is so remarkably improved now, I can live happily with that dysphotopsia (halos).

So, why doesn’t everyone have their cataract IOLs selected to see at near and intermediate distances, rather than at intermediate and far distances? I don’t know. But, if you’re about to have cataract surgery, share this column with your ophthalmologist.

- What is a Cello Madness Congress? - May 5, 2022

- Meet Irvine Resident & Young Filmmaker Ethan Chu - January 11, 2022

- Is the Long-Promised State Veterans Cemetery in Irvine Dead? ABSOLUTELY NOT! - August 8, 2021